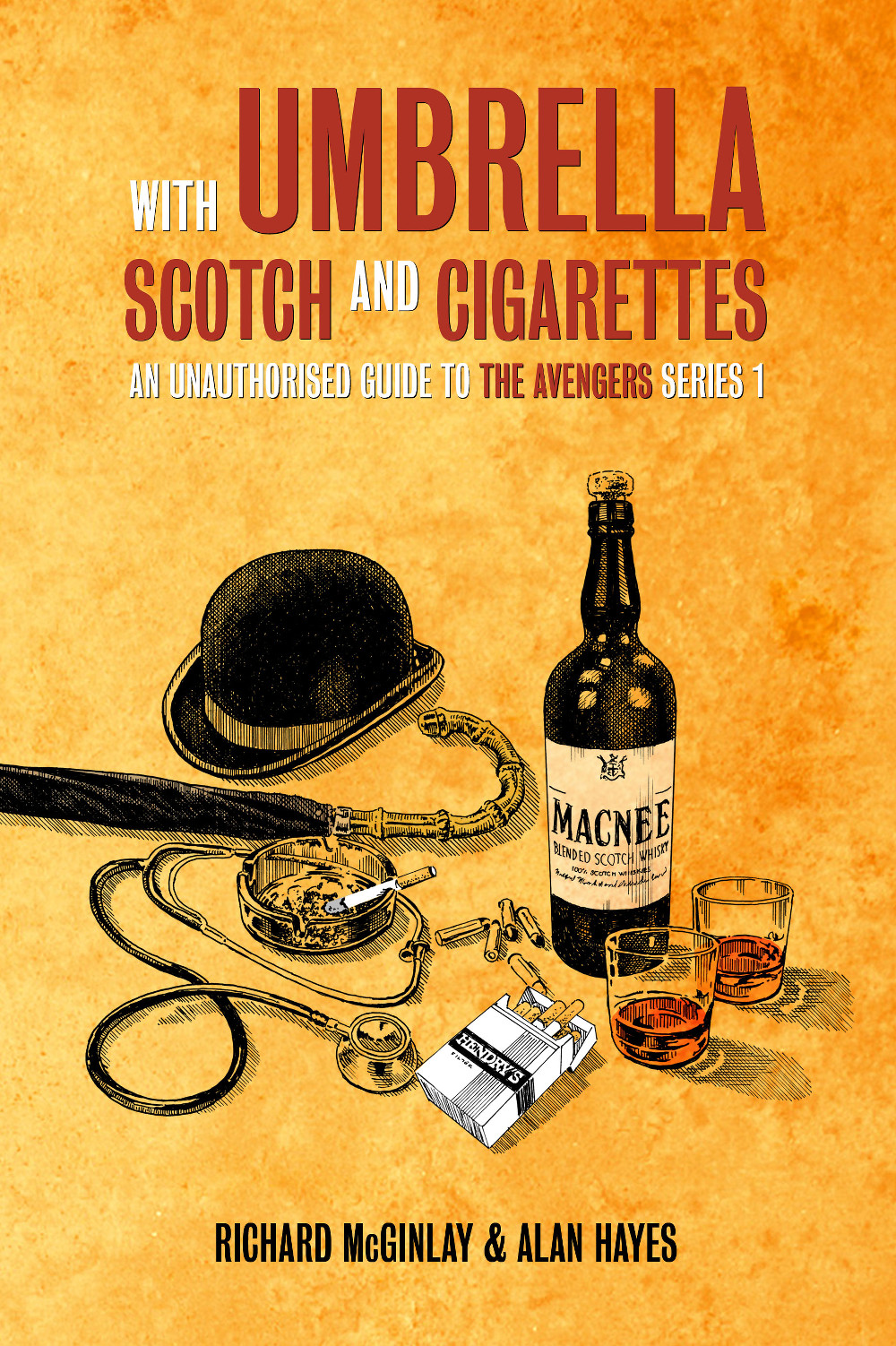

With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes

In an exclusive extract from their new book With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes – An Unauthorised Guide to the Avengers Series 1, Richard McGinlay and Alan Hayes take us through the choices ABC made before and during the first series of The Avengers.

Even though it had originally been planned that Hendry’s Police Surgeon character should continue into The Avengers, there appears to have been a general undertaking that he should step back from his direct association with the authorities. To facilitate this, Brent would fall back on his ‘day job’ as a general practitioner, ceasing his work with the Metropolitan Police. It was felt that the central character’s close working relationship with the police had shackled Police Surgeon to the mundane, and the intention was to make The Avengers much more dynamic and far less predictable.

Once it had been decided not to retain the link to Police Surgeon, Hendry’s character was renamed Dr David Dent, and it is this name that appears in the earliest draft script of ‘Hot Snow’. This was, however, changed at the insistence of Ian Hendry, who felt that audiences would confuse the new character with Dr Brent, the old. The name that was finally settled on was Dr David Keel. By this time, it had also been determined that Keel would experience a cathartic event early in the first episode: he would witness the brutal murder of his fiancée, Peggy. This tragedy would prove to be the catalyst for him becoming involved in crime-fighting.

Character outlines written prior to the series’ first transmission appear not to have survived, but one issued by Leonard White on 31st October 1961 as a reminder to writers reveals the following about Dr David Keel:

Keel, being a doctor, is the ‘amateur’. This does not mean that he is less good at the ‘job’, but simply that his motives for concerning himself with a mission are quite different from Steed’s. Without being at all ‘goody-goody’, he will, usually, be fired by a sense of public service, kindled by his humanitarian instincts. He is an excellent doctor and this proficiency is a specific help in the joint missions.

Women find him very attractive. Usually, however, he will keep them at a distance. His sincerity does not allow him to flirt and he still has deep feelings for the fiancée he lost.

Despite the obvious parallels existing between doctors Brent and Keel, Ian Hendry was very positive about the role when he spoke about it in December 1960: “Keel is a most attractive character,” he said. “He combines just the right amount of toughness and compassion. Keel will be a kind of extended version of the police surgeon, because he will be more directly involved with fighting crime. And as he tangles with the villains himself, he will have more action. Frankly, I thought twice when I was asked to start out on another series as a doctor, but as I know that the accent in the scripts is on authenticity, I think it will do me a lot of good. And I know it will be a lot of fun.” (TV Times No. 270, 30th December 1960)

Leonard White’s character description for Keel echoes the themes of toughness, action and humour:

He is tough, but not hard. Can be very gentle: loves children. Likes sport (would be a keen rugby player if he had the time). Product of a ‘red-brick’ university. A wry sense of humour. Quite serious normally, but when he smiles – it’s wonderful. Being a doctor, he is well trained to think out a problem and resolve it by positive action.

Meanwhile, the character of John Steed, Keel’s enigmatic, persuasive and often difficult liaison with the authorities, is described thus in Leonard White’s document of 31st October 1961:

Steed is the professional undercover man. He is suave, debonair, ‘man-about-town’. A sophisticate, but not lacking in virility. His ‘sports’ are probably horse racing, dog racing, beauty competitions, etc. He has an eye for the beautiful and unusual – be it objets d’art or women. He will never be serious with one woman, however. He is very experienced.

The document goes on to detail his proficiency in armed and unarmed combat and notes the fundamental difference between the professional Steed and his amateur and unofficial partner, Dr Keel.

His motives are not necessarily as ‘moral’ as Keel’s. To him, the success of the mission is the only important thing and therefore his means may sometimes be questionable. The success of the mission is, however, a wrong put right, and therefore sometimes necessitates these means being used to this end.

To all intents and purposes, when on a mission, Steed is his own man. He is highly paid to do his job, and is expected to produce results, independently and discreetly. He answers to an organisational contact, such as One-Ten, from whom Steed often receives briefings on missions and pertinent information.

Once on an assignment, however, Steed (and Keel) are essentially relied upon to work out their own salvation.

Keel and Steed are essentially undercover. They are not private or public detectives, and any story which follows the usual ‘private eye’ pattern is not right for us.

When asked about the character of John Steed in December 1960, Patrick Macnee responded: “The undercover man I play is a wolf with the women and revels in trouble. He doesn’t think so much about saving hoodlums as just getting them out of the way. By the same token, he doesn’t follow the Queensberry rules, and although he works indirectly with the police, he is not too popular with them.” (TV Times No. 270, 30th December 1960) Macnee’s description of Steed’s ruthlessness and womanising demonstrate that, although the surviving Series 1 guidelines hail from 31st October 1961, these characteristics had been established at a very early stage.

Even so, Macnee initially struggled to get a proper handle on the character. Early in pre-production on Hot Snow, director Don Leaver presented the actor with a copy of Ian Fleming’s debut James Bond novel Casino Royale, suggesting that Macnee would do well to draw inspiration from Fleming’s secret service agent. However, the novel was not to Macnee’s tastes, and was, he felt, “the opposite of what I was interested in. Bond used women like battering rams and seemed intent on drinking and smoking himself to death.” (The Avengers and Me, Dave Rogers / Titan Books, 1997)

Consequently, Macnee decided to take a different path with the character, as he explained in 1995: “I took the veneer of Bond for Steed, without using the core. What I left out were the words ‘licence to kill’. Steed had no licence to kill. All I really had as Steed was this iron will to bring the enemy to book.” (The Ultimate Avengers, Dave Rogers / Boxtree, 1995)

In ‘Hot Snow’, Steed is depicted with a deliberate ambiguity, the intention being that neither Keel nor the audience would know whether this man could be trusted. There is even the suggestion that he may be working for the Big Man and is manipulating Keel in order to tie up loose ends for the gang leader. “At first, you never quite knew if he was good or evil,” Macnee recalled. “He was a shadowy sort of character who emerged through windows with a pistol and impeccable brolly.” (The Ultimate Avengers, Dave Rogers / Boxtree, 1995)

In ‘Brought to Book’, Steed is somewhat closer to the character with which audiences would become familiar, cracking jokes and flirting with women – but according to Macnee himself, there was still something missing: “I hadn’t actually thought about Steed in any great detail until, after about two or three episodes, Sydney Newman called me into his office and forced me to take stock of my position.” Newman suggested that the part as Macnee was playing it was just not working; Steed lacked personality, and neither the character nor his costume was interesting enough. He asked if the actor could spend some time thinking how the character and his apparel might be revitalised. “I was terribly downtrodden to hear this – I thought that I was doing rather well – and got very angry and stormed out of his office. Depressed, I went home to my flat and thought of how I could improve the character, rationalise it, make it work.” (The Avengers and Me, Dave Rogers / Titan Books, 1997)

“What the devil did he mean?” Macnee wondered. “John Steed was more than a part of me, he was an extension of myself. And that ‘self’ had been shaped by 18th- and 19th-century influences.” The film director Michael Powell had described the actor as “an 18th-century man”, much to Macnee’s delight. “My clothes were elegant but in such a conventional way as to make them thoroughly uninteresting. Steed’s daring conduct had to be complemented by his clothes.” (Blind in One Ear, Patrick Macnee and Marie Cameron / Harrap, 1988)

For his inspiration, Macnee looked first towards his father, Daniel, the racehorse trainer: “He was a real dandy. He used to lean over the paddock gate, always with a beautiful carnation in his buttonhole. He’d wear a cravat with a pure pearl in it, and wore a lovely brocade waistcoat… Then I ‘pinched’ a bit from Sir Percy Blakeney, the Scarlet Pimpernel, one of the great British heroes. It seemed to me that if Steed was this shadowy person who was helping to rescue other people, he was something like the Pimpernel – somebody extremely well-dressed who gave the impression of being a fop, so nobody felt that he was a threat.” (The Avengers and Me, Dave Rogers / Titan Books, 1997)

Another source of inspiration was the 1939 film Q Planes (released in the United States under the title Clouds Over Europe), and specifically the role played in it by Ralph Richardson, one of the great talents of the era. His character, Major Hammond, a British spymaster seeking to discover the truth about warplanes that had gone missing on test flights, conceals a keen intellect behind the façade of a buffoon, wears a homburg hat and carries a furled umbrella – the parallels with Steed are plain. Macnee has also often credited Bussy Carr, his commanding officer in the Royal Navy, as a further influence on his thinking when defining the characteristics of Steed, someone who was, like Macnee’s father, a dandy, and yet courageous.

The likes of Beau Brummell also sprang to mind. “I thought of the Regency days – the most flamboyant, sartorially, for men – and I imagined Steed in waisted jackets and embroidered waistcoats. Steed I was stuck with as a name, and it stayed. Underneath he was steel. Outwardly he was charming and vain and representative, I suppose, of the kind of Englishman who is more valued abroad. The point about Steed was that he led a fantasy life – a hero dressed like a junior cabinet minister. An Old Etonian whose most lethal weapon was the hallmark of the English gentleman – a furled umbrella.” (The Ultimate Avengers, Dave Rogers / Boxtree, 1995)

Due to the paucity of surviving images from the earliest Avengers episodes, it is impossible to know for sure when Steed’s new look was introduced, though even as early as the third episode, ‘Square Root of Evil’, there is evidence of the agent’s emerging sartorial elegance. The character of Jackie Warren (Vic Wise) mentions Steed’s “clobber”, and says that, “I heard you was something of a dresser.” However, he could be referring to Timothy James Riordan, the forger who Steed is impersonating.

Certainly by the 15th episode, ‘The Frighteners’, the earliest surviving appearance by Macnee as Steed, the agent has started wearing the famous bowler hat and carnation, and is carrying his distinctive whangee-handle umbrella, though these are not regular accoutrements at this point in the series. In fact, judging by the way in which his scene with the Flower Seller (Eleanor Darling) is performed, it is possible that she decorates Steed’s buttonhole for the very first time! It is less likely that this episode marks the first appearance of Steed’s bowler, since his wearing of it passes without comment. Earlier episodes provided the character with arguably more logical reasons for adopting the guise of a city gent – specifically when he poses as an insurance company representative in ‘Ashes of Roses’ and as a cipher clerk in ‘Please Don’t Feed the Animals’. On the other hand, perhaps the production team deliberately allowed the hat to be introduced without explanation in ‘The Frighteners’, simply to be zany. It is worth noting that another character, the villainous Benson (Peter Madden), wears a bowler hat two episodes earlier, in ‘One for the Mortuary’, so it could be that the inspiration came from there.

By June 1961, Macnee was describing Steed to the press as rather more of a fantasy figure than he had been before: “Like Steed, I live by my own rules. I always have. At Eton College I was a gambler, a successful one because I got tips straight from the ‘horse’s mouth’ – my father, then very active in the racing business. I had £200 in the kitty when the authorities caught me. I was nearly expelled. Let’s say Steed is a slightly exaggerated form of myself. Somebody once said to me: ‘you should have lived in the 18th century’. I agree. Like Steed, I’m a great pretender. Anybody who loves the good life, as I do, has to be a pretender.” (TV Times No. 296, 30th June 1961)

Some years later, Ian Hendry summed up his take on the characters that he and Macnee had evolved: “I do think we managed, in those early days, to develop a new style. I was supposed to be phlegmatic, and when I got too boring, Steed was there to send me up and tell me not to be so serious. And when Steed got too outrageous, I was there to say: ‘Oh come on, don’t overdo it.’ ” (TV Times Souvenir Extra – The New Avengers, 1976)

With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes – An Unauthorised Guide to the Avengers Series 1 by Richard McGinlay and Alan Hayes is available from Amazon.co.uk and direct from Lulu – use promo code FWD15 to save 15% on your Lulu order.

The text in this article is © 2014 Richard McGinlay and Alan Hayes and is not included in Transdiffusion’s usual Creative Commons licence.