Contracts and criticism

ABC’s Howard Thomas on the ITA, Pilkington and Lew Grade

To return to the period when The Avengers was launched in 1962, we find ourselves at one of the milestones of Independent Television, the year of the Pilkington Report which lauded the BBC and lashed ITV. Such was the heritage awaiting Lord Hill when in 1963 he was appointed Chairman of the Independent Television Authority for five years. He dismissed the Report with the words:

‘Undeniably the Pilkington Committee has been brutal in its criticisms, so brutal in fact that the Government, sensing that the BBC could not be so white nor ITV so black as Pilkington asserted, had rejected its main recommendations.’

Only a few weeks before Lord Hill took up office the Postmaster-General had declared his intention of opening a second Independent Television service:

‘If all goes well and there are suitable companies willing to offer their services to the ITA, the Government would certainly hope during the autumn of 1965 to authorise the physical build-up of the second programme, starting in the areas of big population.’

On this premise, the Authority extended its programme contracts by another three years, until 1967. Beyond that, said Lord Hill significantly, ‘Present companies and new companies are to apply for any area they choose. All bets are off and there will be a fair field for all.’

On their tenth birthday the ITV contractors were given a package which was unwelcome but not unexpected; the imposition of a Government levy on advertisement revenue, to curb the excessively high profits the companies had been enjoying. But there was also a consolation prize from the Prime Minister; at the celebration dinner in the Guildhall, when he recalled the controversy which had surrounded the inauguration of Independent Television, Mr Wilson paid this tribute:

‘Today, ten years later, on one thing all of us here tonight can agree. Independent Television has become part of our national anatomy. More than that, it has become part of our social system and part of our national way of life.’

By this time ITV was indeed a fixture, with an audience of fifteen million homes, reaching eighty-one per cent of the population.

The companies were paying the Authority £8,000,000 annually in rentals and £22,000,000 in levy out of a net income of £75,000,000. Within ABPC, ABC Television had grown taller in stature than its parent.

In spite of forebodings in the boardroom, ABC Television in its first full financial year had made a small profit for its owners. Thereafter it had contributed increasingly to the total profits, rapidly overtaking then passing the combined earnings of the cinemas, studios, productions, catering, and bowling centres. The trading profits of the group in 1963 totalled £4,035,987, of which ABC Television contributed £2,622,562. A year later ABC Television’s profits had grown to £3,337,185 and the Corporation’s profit had swollen to £5,246,439, while profits from the cinema side had shrunk to £1,982,256. Rewards came to us all in time and at the end of 1964 I was at last elected to the parent board of ABPC. The only financial effect of this was that I was invited to buy 730 shares in the company, at the market price.

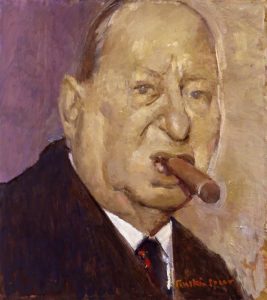

The overall scene was changing. Val Parnell, in his seventies, had retired to the South of France. Lew Grade was the undisputed king in full control of the ATV empire. Lance-Bombardier Louis Grade, Royal Signal Corps, as the identity bracelet on his wrist proclaimed; dancer and Charleston champion; theatrical agent and Deputy Managing Director of ATV, had reached the summit and was now at his tycoon peak. ATV had become a one-man concern, even with its 1,700 staff and electronic studio in Elstree and skyscraper in Birmingham. Though there was a succession of personal assistants, assistant managing directors and deputy managing directors, the job of number two at ATV never seemed to be a permanent one.

by Cornel Lucas 1996

As Lew expanded his activities, with tremendous energy and courage, developing his other business of providing popular filmed series for the American market, taking over Pye records and assuming control of the theatre side of the business, he took on the tasks of three men. Now he had the big office high in Cumberland House to himself, sitting in the corner where Val Parnell used to be, backed by the handsome bookcase with the English classics in beautiful bindings (though the ones I occasionally took out contained no pages). Lew installed his own king-size desk, full of locked drawers crammed with costing sheets and contracts. In one drawer he kept a wad of unpaid invoices with which he would confront me and I would claim we were being overcharged. In the middle of the desk between us would be a large old-fashioned hand telephone; my occasional assertion that this was bugged was a guaranteed way of making Lew lose his temper. There were times when I thought he was going to explode with anger or excitement, but I learned how to calm him down. His method of pacifying me was to offer me one of those titan cigars, which I never accepted, although if I had kept them all I could have opened a cigar kiosk at the Hilton. Usually we met at the beginning of the day and Lew’s secretary would produce a steaming bowl of coffee with sweet biscuits, which was the boss’s breakfast. A light eater and a teetotaller Lew still had trouble with his chubby waistline and when he did lose some weight he liked to demonstrate that his trousers were getting too slack for him. Tea was another of his social occasions and once he said to me on the telephone with delight: ‘Who do you think is coming to tea with me? Bette Davis!’ The eternal theatrical agent, he was still bedazzled by star names, glittering or otherwise. Our conversations were mostly arguments about money and the buying or selling of programmes. His repertoire was as varied as a cinema organist’s, and he could pull out all the stops – sentimental, threatening, pleading, admiring. His best act was when he would go down on his knees and fling out his arms, one hand still gripping the cigar.

Lew’s birthday was on Christmas Day, and in fact most of the family had their birthdays on noteworthy days of the calendar. Lew’s brother, Bernard Delfont (now Lord Delfont), once explained to me the reason for this. When the family emigrated from Russia and came to East London there was some confusion about their birth certificates. Their mother, Mrs Isaac Winogradsky, could remember only the years when her boys were borm but not the actual dates, because of the Gregorian calendar, and this left them scope to select their own birthday. As the firstborn. Lew exercised his option to choose December 25.

In the agency business Lew and Leslie Grade were in direct competition with Bernard but any real rivalries must have dissolved when they all met at week-ends in the matriarchal home in Wimbledon. Illness reduced Leslie’s activities but there were many healthy differences of opinion between Lew and Bernard. Lew became essentially a television man and Bernard a man of the theatre, but they both had burning ambitions to get into the film business. When EMI finally absorbed the Grade and Delfont agencies Bernard became Chairman of the group’s film production and theatre interests and therefore got in first. Some years later, when Lew became disenchanted with the declining profits of Independent Television he, too, went into feature films, with a blast of trumpets and lavish press receptions. Lew, to me, had always been ITV’s Sam Goldwyn and now he was following exactly in the steps of the film mogul. I used to say that at his television press conferences Lew usually doubled the figure he first thought of; but when he went into films his multiples grew more expansive and we began to read about budgets of fifty million dollars.

In some ways, too, Lord Grade probably was missing the early triumphs and setbacks of ITV, which never ceased to be a stimulant. We still worked in close collaboration on industrial affairs, and always sat together at the monthly meetings with the other companies and with the Authority. As we both gradually hannded over the direct control of programmes to our own able executives and as we yielded our seats of power at the Independent Television Companies’ Association Council meetings and the Standing Consultative Committee gatherings at Brompton Road, some of the zest for television probably faded in both of us.

Even while he had still been concentrating on television, Lew as a one-man operator diversified his activities with his regular trips to the United States to sell programmes, as well as controlling the other ATV activities. This lessening of attention to the ATV franchise in Birmingham and London gave us our chance to move in and ABC Television was able to concentrate on its single objective of improving our strength within the network.

As we analysed our strengths and weaknesses we tried to see ourselves as the Authority saw us. We wanted to prove that we had the potential for a bigger contract and for weekday television. We had the staff, the executives and the programmes, as well as the studios, notably Teddington, which had become the most advanced television engineering centre in Britain outside the BBC. The experiments with colour in the studio had given the staff exceptional experience, well in advance of the Government giving the signal for ITV and BBC to transmit colour.

The era of black and white television was coming to an end. So was the original pattern of ITV. Changes were on the way and new pieces had to be fitted in to the jigsaw.

Lord Hill was now put in command of the Authority. No longer was the Director-General totally in control, gently guiding his Chairman. Those of us who had worked at the BBC knew well how the course of the Corporation had fluctuated over the years as the controls changed hands between Directors-General and Chairmen. Now, after more than a decade of subtle steersmanship there was a new and powerful hand at the ITV wheel: by joining all the committees (although not always in the capacity of Chairman) and spending four mornings of every week with the Authority at Brompton Road, Lord Hill became as fully informed as his Director-General.

The companies all realised that changes were in progress and we speculated as to where the axe might fall. It was obvious that the deadline for announcing any changes in contractors would have to be decided before the Authority’s year ended in July, 1967. Therefore no-one was surprised when Lord Hill chose the end of February to reveal his hand. He explained that a fifth major networking company would be introduced, in Yorkshire, and would be allocated a seven-day week as well as the existing Lancashire and Midlands stations. London could continue to be split, but on a slightly different basis, with the lucrative Friday evening added to the Saturday-Sunday contract. The London weekday contract would thus be reduced by its most remunerative evening of the week. This new arrangement, a genuine attempt to divide the three central areas fairly and evenly between five companies would eliminate the North and Midlands weekend contract.

Applications were invited for all the fifteen contracts and we were reminded of Lord Hill’s statement in 1963 – ‘a fair field for all’. Now, in 1967, the Authority intended ‘to select companies for the award of new contracts, and not merely to consider the renewal of contracts’. This, I knew, was ABC Television’s opportunity to become a London programme contractor. We would apply for the London Weekend contract, bringing with it the additional Friday evening revenue which would help to subsidise our expansion into weekday programming. We had the least to lose, perhaps the most to gain.

About the author

Howard Thomas (1909-1986) was a writer, producer and television executive. He was managing director of ABC Television throughout its existence and held the same post at Thames Television until the early 1980s. His autobiography, 'With an Independent Air: Encounters during a lifetime of broadcasting' was published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson in 1977.